Authors of the short book Reading Bestsellers: Recommendation Culture and the Multimodal Reader, Danielle Fuller and DeNel Rehberg Sedo, join us for this month’s episode to talk about their research into the relationship readers have with bestsellers and what they found from their qualitative work with a group of international Gen Z readers.

Want to make sure you never miss an episode of the podcast? You can subscribe for free on iTunes, Stitcher, Pocket Casts, TuneIn, or SoundCloud.

Further Reading:

Reading Bestsellers: Recommendation Culture and the Multimodal Reader by Danielle Fuller and DeNel Rehberg Sedo

Transcript:

Ainsley Sparkes: Welcome to this month’s episode of the BookNet Canada podcast, I’m your host, Ainsley Sparkes, Marketing & Communications Manager here at BookNet. In this episode, I spoke with the authors of a recently published short book, Reading Bestsellers: Recommendation Culture and the Multimodal Reader, part of the Cambridge University Press Elements in Publishing and Book Culture series. Danielle Fuller and DeNel Rehberg Sedo spoke to me about their research into the relationship readers have with bestsellers and what they found from their qualitative work with a group of international Gen Z readers.

Can you introduce yourself and tell us a bit about your professional background that brought you to this research?

Danielle Fuller: My name is Danielle Fuller. I started off my academic career as a literary studies prof. All my degrees are in English literatures. In fact, my PhD was in Canadian literature, and I spent 20 years teaching Canadian studies and Canadian literature at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom before I emigrated to Canada in 2018. Now I work at U of A, University of Alberta, in the English and film studies department.

But the thing that really brought me to thinking and researching about readers and contemporary cultures of reading was from way back when, really, because before I was a graduate student, I worked briefly in publishing in London for what was then Random Century and became part of Random House. And once I had worked with authors and editors and publicity departments, I never really thought about books in the same way again.

So, I think that really sowed the seed for thinking about how books are produced, all the people, all the different agents who help to put a book into the world and into people's hands. And then, increasingly, as time went on, I got really intrigued about how readers outside of universities were taking up books, what they thought about them, but also how they shared their reading and reading experience with others. And that's kind of how I came to meet DeNel.

DeNel Rehberg Sedo: And I'm DeNel, DeNel Rehberg Sedo. I am a professor at Mount St. Vincent University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and have actually spent my entire 21-year career here, having been hired while I was doing my PhD thesis work or dissertation work in Canadian women's book clubs. At that time, book clubs were not part of scholarly endeavours. And I had come to my PhD project with the other project in mind, and that wasn't working as well as I had hoped, so I thought, "If I'm going to stay in this programme, what is it that really intrigues me and interests me?"

And I had been part of a reading club or a book club for maybe a year or two. And we were talking and thinking about books in ways that were enriching all of our lives, and so I thought, "There's something about this." There's something about people coming together and talking about the books that they're reading. And so I switched my focus of my PhD and have been studying readers ever since.

At that time, nobody had really looked at book response or reading response in online environments, and so I used that as part of my PhD research and have followed that trajectory ever since. And to my good fortune, received an email from Danielle 2003, 2002. And she said, "Hey, I just finished my PhD, and I'm interested in shifting into studying readers." And we've been doing that ever since. So, that's how I came to it.

Ainsley: It's very interesting. In your short book, you do a lot of talking about books, you know, as products and the producing of books, which sounds a little bit, Danielle, like your background from publishing, and then also, like, the reader experience and the feelings about books, which sounds, DeNel, a little bit like your experience through your PhD journey. So, I guess that's a little bit about what led you to wanting to do some of this research. But what led you to, like, wanting to research bestsellers in particular and the reading attitudes towards them?

DeNel: We never really thought that we would focus in on reading bestsellers, but we were approached by colleagues and asked to write about it. And we have always started our research from the perspective of readers. So, creating our research questions about readers themselves and looking to the data and what readers tell us instead of trying to impart prescriptions on the readers and their responses.

And so we were a bit hesitant, I think. Is that right to say? We were a bit hesitant about taking this on. I'm glad we did because it took us through the pandemic. We started it before the pandemic. We were able to follow up on a 2007 research project that we based our first book on and look at comparatively how readers responded at that time and how they're responding now.

We were able to interview influencers, which was a great joy. And even more so, I don't know if it was a bigger joy, but very much fun as we spent two months in Instagram in a private chat group with readers from around the world, young readers from around the world. So, it was a very enriching research experience. Danielle, you want to add on to that? Because it was actually you who convinced me to do this with you.

Danielle: Yes. I had to kind of...first of all, as DeNel said, it was a commission. And we had never really been approached and given such a clear brief before. And so these are colleagues of ours, led by Beth Driscoll from the University of Melbourne, three of our Australian colleagues, who are interested in how, particularly in popular genres, in genre fiction, like romance and crime thrillers, and have done a big project together, looking about how those are produced, particularly in the Australian context. And so they proposed a kind of, like, mini-series within Cambridge University Press's Elements, specifically on bestsellers. And so I sort of said, "Sure. I'll do the one on 'Reading Bestsellers,'" thinking, "Oh, I'm sure I can persuade DeNel into this." And then I kind of pitched it to her.

But one of the constraints for us was that our Australian colleagues had set the parameters, so it had to be about bestselling fiction in English. So, that was one of our hesitancies because, as DeNel says, we usually start from what are readers thinking about? What are their practices of choosing and selecting books? How are they sharing their reading experiences with other readers? Where is book talk happening online or offline? And we usually kind of follow what readers are doing and take our cues from there. And here was some colleagues saying, "Okay. We want you to fit into this kind of series."

But we decided we'd see it as a challenge. And, as DeNel said, it actually turned out, for all kinds of reasons, to be really fruitful. And I have to say as well that we always intended to do all of the work online, both the questionnaire, and then, secondly, the interviews with influencers, and, thirdly, that we would work with a group of readers on a social media platform that's popular with readers and where book talk happens. And boy, did that set of decisions ever turn out to be fortunate because then, of course, we had no choice because of when we did the work, most of which happened between 2020 and the end of 2021. We had no choice but to do it remotely. So, yeah. So fortuitous, I think, in several ways.

Ainsley: It was already in progress the way that you had to continue.

Danielle: It was lucky, I think. But we also, to be fair, DeNel, very, very early on had written as a scholar and done research, as she mentioned earlier on, was one of the first people to publish anything scholarly about readers using the modality of the online offered. And that was really pre-Web 2.0, was things like forums and very simple book blogging and reading groups that preceded Web 2.0.

So, that interest had always been there. And we've been, in a sense, tracking those histories, how technologies were changing, not just the venues online where readers could meet, as it were, but also how the different affordances of different technologies, as they came on stream, altered the ways that readers could have book talk or share recommendations and so on and so forth.

So, in a sense, the commission also gave us the opportunity to say, "Okay. What does this look like at the very beginning of the third decade of the 21st century when there's a proliferation of social media platforms?" And some of which have been around...things like Facebook have been around since 2005, and Instagram has been around since 2010. So, you know, they've had some time.

And, of course, again, a bit of fortuitous timing, we were doing the primary research when sort of BookTok kind of exploded, really. And as people who are interested in contemporary cultures of reading and how readers use new media and continue to use other offline practices of choosing and sharing their reading, too. So, you know, libraries and brick-and-mortar bookstores and in real-life face-to-face reading groups, all of these things still go on. It's not that the digital has wiped all these face-to-face or analogue ways of sharing reading and book discovery way. Not at all.

So, I think, you know, we're very aware that things move very fast, and we want to always, I guess, take those snapshots in time and stand back and analyze and figure out what's going on because, actually, those kind of early histories of the sort of the internet and, in our case, readers using those earlier forms can get lost really fast as everything moves on.

Ainsley: Do you notice a change? Because I suppose you started your research...I mean, TikTok was around but not nearly as big as it was probably by the end of your research. Did that show up, or was it just basically the same things just in a different platform to a slightly different degree, but, you know, basically the same sort of trends or ways of sharing?

DeNel: Yeah. TikTok was part of the scene. And we knew that BookTok was happening on TikTok, but, of course, it was the pandemic that really catapulted that. And especially for younger readers. But now that's not necessarily the only case because we see lots of different age variations of BookTokers on TikTok.

But we were originally thinking about using Tumblr as a way — because many readers use Tumblr as well. And I think that we made the decision to go into Instagram for the sustained conversation with ... I think we started with 16 readers, and 13 of them completed the whole two months with us. But we made that decision because we saw a dramatic increase of YouTubers turning to Instagram to share their reading experiences. And it gave us the opportunity to create a sort of closed long focus group.

But what we did see ... Let me just back up here a bit. Our survey went out and finished up in February of 2020. So, that actually was really very interesting as well because then the shift happened after the various lockdowns. And so we were able to get a little bit more in-depth with what readers were doing during that period because we went into the interviews with the influencers, and we did sustained, although not systematic, observation of the various social media platforms, including Reddit. A lot of readers are on Reddit.

Danielle: Yeah, of course, each of the social media platforms has different affordances and different functions. BookTok is a very short format, for example, and it has that...you know, it's borrowed that kind of meme-like playfulness from other areas of the internet and other kinds of platforms that came before it. And often, even on BookTok, BookTok is a sort of semi-parodying some of the other social media platforms where book culture lives. They'll mock or be quite playful about those very curated beautiful visual displays on Instagram. Or they'll kind of send them up or satirize them in some way.

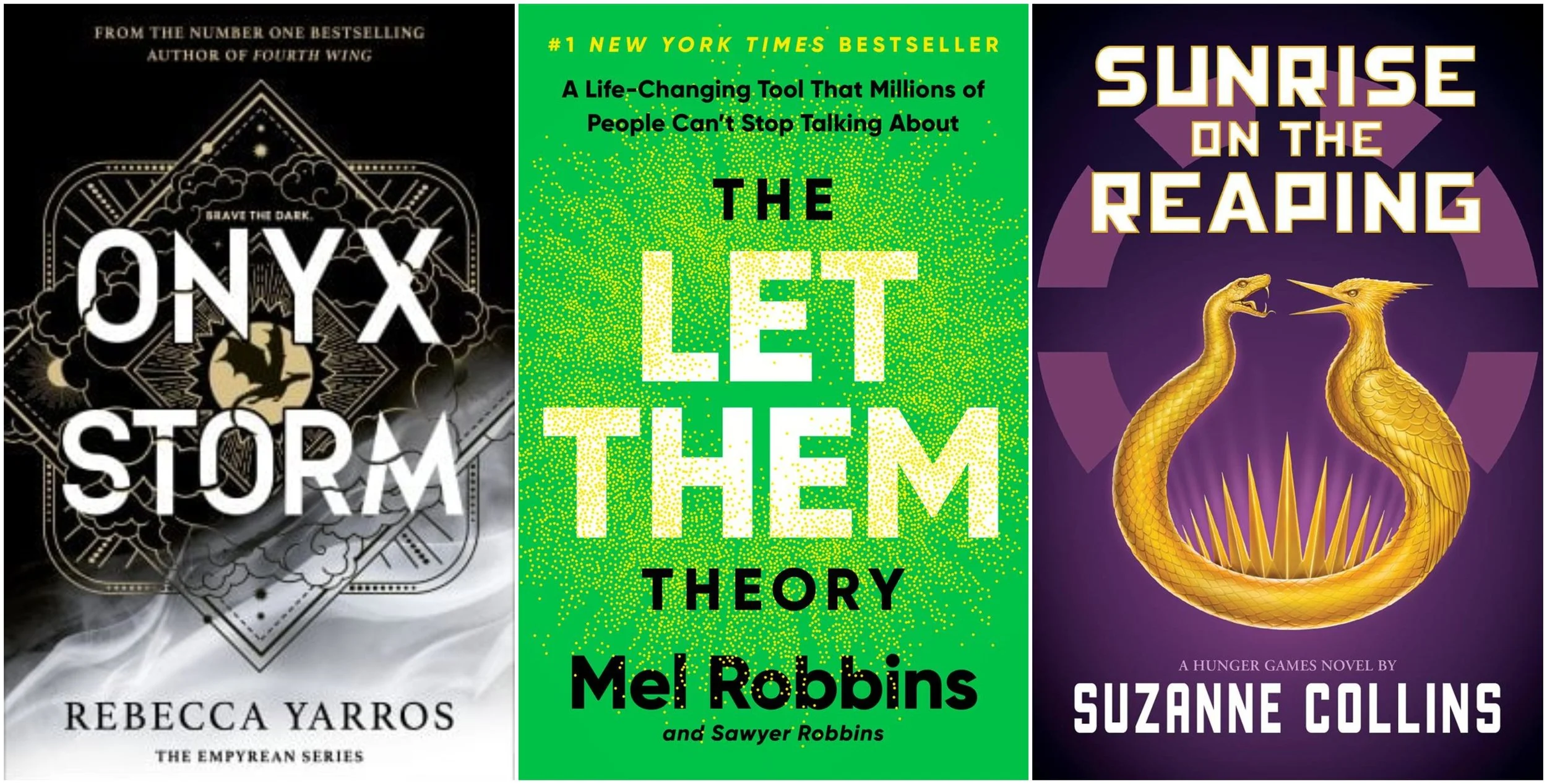

So, I think BookTok is a very playful form, and, of course, it's a short form. It kind of works best when it's quick. It tends to be people take up the different sorts of new modes, like certain kinds of challenges, and different ways of presenting books and copy each other very quickly, you know, like, even sort of commenting on BookTok itself with things like, for example, you know, "10 BookTok books that really aren't worth your time," or that kind of thing.

So, I personally sort of enjoy the tongue-in-cheek aspect, I think, of BookTok. You can see so many of them either borrow or parody some elements from the other platforms. So, often, another example would be people frequently stand in front of their bookshelves or stand in a bookstore in front of bookshelves. And we've seen that, you know, all over Twitter and as well on Instagram. We've seen YouTubers do that, having their bookshelves in their backgrounds or even giving us guided tours of their bookshelves and how they organize their books by colour and genre and those kinds of things.

So, as DeNel said, there's actually a lot of consistency, especially for content creators, in terms of how they kind of curate both their online persona as a reader and how they present books to other readers. And then there's different kinds of things going on, of course, in terms of the type of response that's possible. I think one of the reasons Reddit has such a sort of longevity with readers is because there's no real limit to how much you write. And if you want to write a full-length review and ramble on for sentences after sentence, you can. And many of the other platforms, of course, don't really allow that. You have to be a lot more succinct. You might be able to connect, tagging other people, but you're not necessarily gonna have the more in-depth, "Here's my interpretation of such and such a book," that's possible on a text-based platform like that.

DeNel: Yeah, I think what happens is people know what they're looking for. If you use Reddit, and if you're a reader, you know where to go. Because you've identified the genre that you're particularly keen on and you know how to find the forum that's going to give you ideas on what to read next or give you an opportunity to provide your own review, that sort of thing.

Ainsley: Speaking about finding what to read next, BookNet is just releasing our Canadian Leisure and Reading Report 2022 at the end of May. And in it, we found that word of mouth is down as both a book discovery method and as a reason for choosing to read a particular book. Did you find something similar in your research? And how did the readers that you interviewed talk about recommendation culture?

DeNel: I think we're talking about two different areas of our study. So, I'll just speak first to the survey. The survey went out through our personal and professional networks. So, it's not a random sample. We ended up with a lot of Canadian responses because we both work in Canadian institutions. But our question might have been different from yours because we asked, "How do you choose the books you read?"

And so word of mouth was not one of our responses that were available to our participants. We had friends and family recommendation. We had work colleagues recommendation. And those two, in both our 2007 survey and in our 2020 survey, both of them were in the top five ways of choosing what to read next. To me, that's word of mouth.

But our participants were very sophisticated in how they decided or the genres that they noted that they read. So, maybe your participants were more sophisticated in what word of mouth means. Does that mean, like, personal face-to-face word of mouth, or does it mean social media word of mouth? So, I think we have to be careful in comparing the two.

Danielle: True. Because when we had done the earlier work, questionnaire survey work, it really was pre-social media. So, we thought that was a really good opportunity to ask some of the same questions, you know, "What's your favourite genre to read? How do you choose books? Where do you get most of your books from?" By the way, the library did very, very well in both of the surveys, in 2007 and 2010. Libraries loomed large.

I think when we got to the more qualitative work, the work, for instance, that we did with the young adult readers who were aged between 19 and 26 and lived in...I think they lived in 13 different nation states and in the global north and the global south, there we could see, we kind of could dig in a bit to how they were making sense of different book discovery methods because they were all eager to talk about it and share some of the ways that they generally find books.

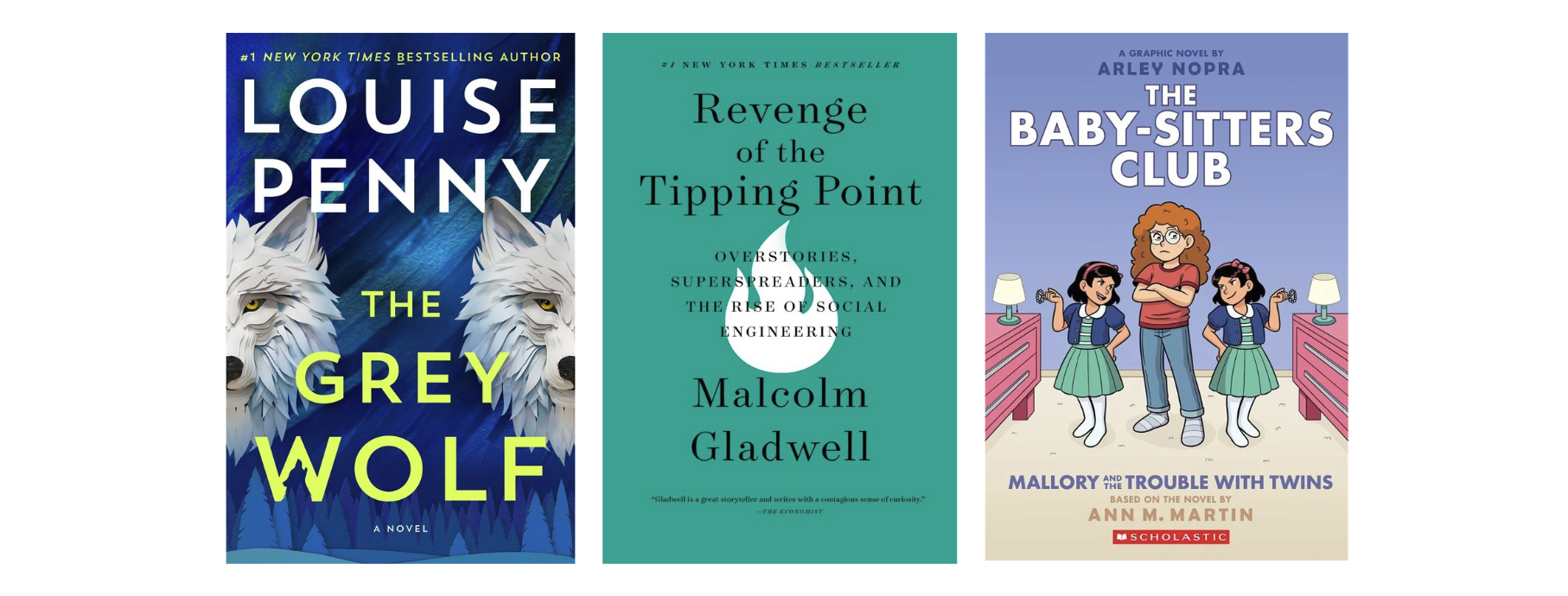

And we set them a task of selecting a work of bestselling fiction in English that they would review and then they would share the review. They could review it on any platform that they wanted to, but they had to share it with the group. And one of the things we asked them to do was to share their process of going about choosing that bestseller. And along the way, we got them to talk about how common what they were doing was, where they would normally do that when they were finding a book to read for leisure, because this was like a little bit of research in a sense for many of them, and they really put their researchers' hats on.

Quite a few of them really went to town, checking out multiple bestseller lists, querying what a bestseller even was, comparing across countries what definitions of bestsellers were, and, you know, cross-tabbing their results by going and reading loads of Goodreads reviews, and then trying a different platform and looking up what other readers have said about the book.

So, there, we got a real picture of, you know, how, in a sense...and this may be, again, why people didn't pick word of mouth. Because for some people who identify as a reader...and not everybody who's a reader identifies themselves as a reader, and we always make that qualification. But especially for people who would even go further and say that they're keen readers, they read regularly, and they're book readers, many, certainly, these young people in this particular age group, you know, were very adept at using multiple different kinds of resources for figuring out which book to read next.

So, many of them use Goodreads, but that's just one of the sources for them. They do really care what other readers have to say about the book. But similarly, if they have an influencer that they follow on a particular platform whose taste in books they've come to know and to trust, they will also check out, "Has this person reviewed or recommended that book?"

So, there's more than one mode of finding that next book to read. So, I wonder if there's a little bit of that going on, too, that the word of mouth now, it's like, what does that even mean now? People also commented, you know, this was a book, one young person, you know, talked about a particular book and said, "Well, that was all over my Instagram last year, at least for my algorithm." So, showing them that they had that sort of sense of, "I've got books come across my radar multiple times, some of it is computational, some of it is about algorithmic culture." It's not necessarily about overt marketing by a publisher or even what other readers are recommending. So, there's that mixture of things going on that they were very aware of.

So, I think, yes, what does even word of mouth mean now? People may not even be able to pinpoint, "Where did I first see or hear about that book?" I think that was something that really came through with that group. You know, people were like, "Well, maybe I saw it reviewed on BookTube because a couple of people I follow there," or, "Maybe my friend recommended it. Maybe I saw a library display." I think that's what's changed, whereas perhaps in the early part, even, of the 21st century, word of mouth probably still meant, you know, the friend's recommendation, or my book group's recommendation, or, you know, some family friend, you know, who has similar tastes in books to me gave it to me for my birthday.

Ainsley: Back to the point about researching what a bestseller is. I thought that was really interesting. We have a blog post that we wrote back in 2018, "What Makes a Book a Bestseller?" And it's, like, one of our top-visited blog posts every month. It's funny because working in the industry, you just sort of understand what a bestseller is, and you think everybody knows, but it is kind of an opaque thing. And it does mean different things in different places.

DeNel: It's a very interesting term. You could be very basic about it and say that it's an industry term. Most of the readers that we've talked with are very, "What is a bestseller?" They're very, very questioning of it. Like, "I don't know if I read bestsellers." That's why I even hesitate to take too much credence in our findings and the percentage of the books that you read. I think one of our questions was something about of the books you read, what percentage of them are bestsellers? Because people don't really know how they define bestsellers.

We had an open-ended option on that. The way that we had designed that question was, I think that we said something, "What do you think of when you think of a bestseller?" And we had actually used a variety of terms that we had come across in our research careers. And there were options from “publisher bumf” to “good quality, dependable”. And I'd say half of our participants actually took the time to write in extra stuff about the terms or the concepts that they had attributed to bestsellers.

Danielle: Yeah. So, in the survey, we had over 3,000 responses. So, we had just short, I think, of 2,000 people, right, just freeform writing their perceptions about bestselling fiction. And even after having chosen one of our many varied options. I think what we got out, particularly of that part of the survey, was that bestseller is a very polarizing word for readers. And as we began the book, you know, no reader ever says that or identifies bestsellers as their favourite type of book to read.

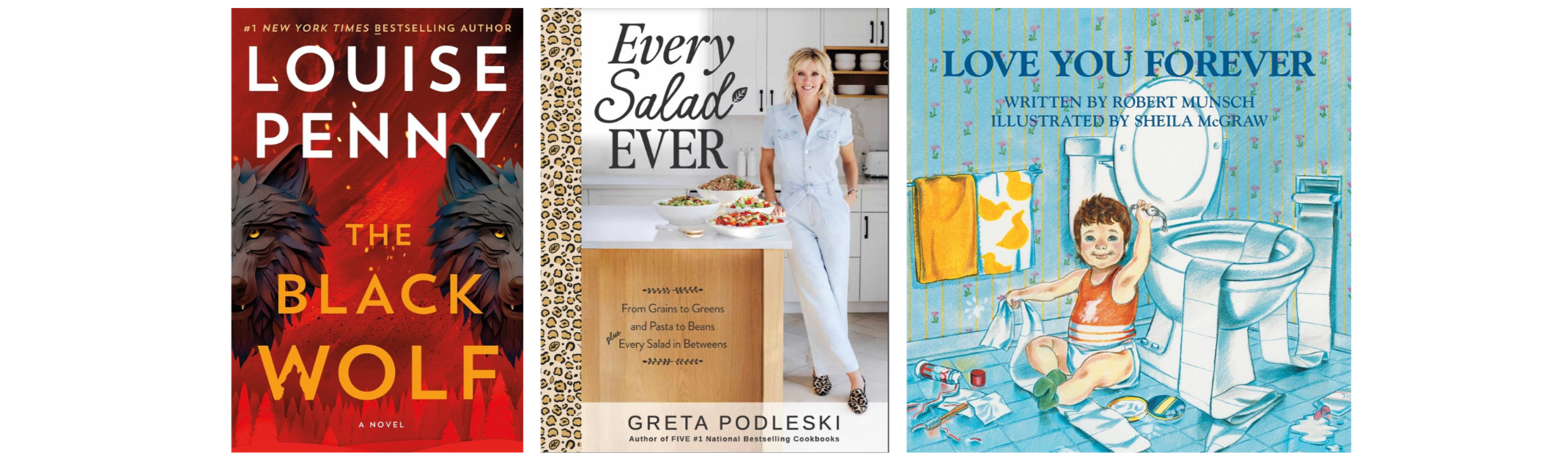

And that's partly because of what DeNel said, that best readers will often query, well, what is a bestseller anyway? Do you mean those big brand-name authors, like Stephen King and Colleen Hoover? Or do you mean this book that sold in, you know, quite considerable amounts because it won a literary prize, like the Governor General's Award or the Booker Prize? Or do you mean something else? Do you mean a BookTok book, like "The First to Die at the End" by Adam Silvera, which became a bestseller because of BookTok, you know, some time after it had already been published?

So, it always exemplifies, I think, readers' responses and their perceptions of bestselling fiction in particular. The kind of tensions between books as a commercial product and books as a cultural product or form of expression. And so a lot of the sort of the rejection of bestsellers is often because bestsellers are perceived to be something that sells, that's commercial, that sells in high volumes, that gets a lot of publicity money and dollars thrown at it by publishers, that, you know, you can't avoid. Wherever you go, you see posters in bus stops, you see advertisements in magazines, you see it all over different social media feeds. And that kind of blatant publicity and commotion can really put some readers off.

But then, again, the obverse is also true, and, literally, the readers who responded to the survey part of our work just fell into two halves. And half of them were saying, "Bestselling fiction, that's, you know, trash. I avoid it. It tells me what not to read when I see that label on something." Versus the other half, who were kind of, you know, "That means, you know, lots of people are reading it, so I want to check it out. I want to go to the library. I want to do more research. I want to figure it out. Or, you know, that could be a good read for me when I'm feeling tired or I'm on the beach, or, you know, I want to be involved in reading something other people are reading."

And then everything in between, which was much less evaluative. There were people who kind of just said, "Well, you know, they’re a books that's met with a certain kind of success, and maybe sometimes that success is to do with money and sometimes it's to do with the quality of the writing and something being well reviewed." But for readers, it's very polarizing, I think, as a term. It usually gets quite a strong reaction.

And I should perhaps say here, too, that because we were given the parameter of bestselling fiction, we had to keep emphasizing that. But DeNel and I would be the first to say, as people who research readers and work with readers, that, of course, readers read all kinds of things and all sorts of different genres, nonfiction genres and fictional genres, for example. So, people who read books, certainly, and this is consistent in the work we've done over the last 20 years, even the most avid fiction readers usually have a nonfiction genre that they really like to turn to as well, that might be memoir, it might be history, it might be food writing. That's consistent.

And of course, readers read all kinds of things, not just books. They read magazines and newspapers and all sorts of things, other sorts of formats and media as well. So, that's perhaps as well why...that's another reason why readers never say bestsellers is their sort of favourite type of book to read, because it could refer to any sort of number of genres, for one thing, and it's just one, for some readers, among many, many different types of reading material.

Ainsley: I mean, the success of a book does obviously hinge on readers, right? You have to convince them that they want to buy it, read it, and talk about it. So, is there anything in your research that you found that you would highlight for publishers who want to reach readers? And did your readers mention, like, gaps in how the books are marketed towards them or ways they'd want to be reached out to?

And I guess I'm specifically thinking a little bit about diversity in terms of how publishers approach different groups of readers than maybe they traditionally approach. Because, I mean, I think publishers are really good at the mainstream promotion of books, but, you know, the smaller-niche either books or platforms are a little bit more difficult to get into.

DeNel: It was very blatant and very evident right away when we started the Instagram group. Number one, there is such a thing as living in the recommendation culture. Like, people do. That's why the word-of-mouth thing, I come back to that, again, they almost instantly started recommending. Even before they had had an opportunity to bond, they started creating bonds with one another across time zones, and age groups. and ethnicities, and genders by recommending books to one another. Soon thereafter, and Danielle can speak more to this, is soon thereafter, it became evident to us that they were ethical consumers.

Danielle: So, it's important to remember this is a group of young people aged between 19 and 26. And, yeah, they were living in 13 different nation-states in the global north and south. And so they had sort of different amounts of kind of access to different kinds of books, too. So, still a lot of inequities in terms not just of who gets represented in the pages of books, which is something that they talked about as a group. And some of them certainly, particularly readers in Europe, Pakistan, and Indonesia, for example, and in particular, if they happen to come from what was a minority language group in their country, felt that their communities weren't often represented in kind of mainstream books published, especially by the big publishers in English.

So, that sort of politics representation was part of their ethics. Many of them in the group were actively looking for books about people like themselves or their communities. They were also very outward looking as a group in the sense they were interested in other life experiences, other kind of cultural backgrounds that were different from themselves. But they were very aware that the world is not a fair place and that many inequities, you know, that exist structurally sort of economically and politically around the world and between the global north and south often get replicated in the pages of mainstream books, you know, put out, particularly by the big publishers. So, they would go searching for things.

So, that was part of their ethical consumption, that they would recommend books to each other that they'd found, like, you know, they were very concerned about mental health issues, for example. That was another topic that came up several times. And they had recommendations around that for each other, books they felt had done a responsible job of representing particular mental health conditions, for example.

But equally, they were very keen not to buy books from the...well, they preferred to spend their money at independent bookstores if they were gonna buy a book. And some of them had made a deliberate decision that they would only borrow books, even. I mean, none of them had a lot of money because they were all young people, and many of them are still studying, or they're working part-time, or they were looking for a job because they'd just finished university. So, they didn't have a lot disposable income, but even the money that they had, they were thinking very hard about where that money was going.

So, they were kind of ethical consumers in that sense, in several senses. And in some senses, they were a great group because they kind of pushed back against the parameters of that commission we were given because, you know, although they all spoke English, it wasn't everybody's first language, and many of them were multilingual and read in several languages. And so that was one way in which they were querying, really, the dominance of English as an imperialist language. But, also, it was a predominantly BIPOC group, and we had recruited that way deliberately because racialized readers are really underrepresented in reading research that's undertaken in English.

And, you know, I think that's another reason as well, like, readers, they were very invested in helping each other find books that they felt they could identify with and that did a kind of responsible job. So, I think, for publishers, especially with that younger age group, and I would even go younger than that and say 14 years old and up, because many younger teens read so-called adult books, not just YA, these issues are really life to them. Their world is on fire, literally, and so they care about environmental issues. And that's another reason some of them borrow books or, you know, don't want to accumulate lots of material objects. And they're very concerned with those kinds of issues.

I think anything publishers can do to really take seriously, to really listen to the issues that young people are really concerned about, both kind of more personal things about what it's like to sort of grow up now in a world where environmental concerns are a real crisis among several crises, but also where, like, mental health issues are very much into the foreground and where, you know, we imagine the world is smaller and yet some of the differences are larger. And they were very keen to sort of discuss their sort of realities.

So, I think they sometimes felt underserved by the type of books publishers were publishing, and they were very aware that...again, back to the sort of...and some of this is algorithms, and some of it is promotion, that they saw the same kind of books being pushed by the companies that have the money, the publishers that have the money, over, and over, and over again.

So, if I had to say something to publishers apart from that, you know, actually go to some of these younger demographic groups and ask them what they care about. I would also say, you know, don't just go to the same influencers all the time because, I mean, there's plenty of BookTokers and Bookstagrammers and influencers online talking and critiquing the fact that sort of White influencers take up way too much space online, and algorithms exacerbate that. I mean, the platform coding, the way that searching and categorization works, sort of under the hood, replicates lots of structural inequity. So, you know, there's a lot that has to be kind of fixed or fought against, but I think it is possible for publishers to be proactive in actually pushing back against some of that just more and more of the same.

And I think listening to young people...that was the thing I really took away from the group, that they were very articulate about the things they were concerned about. And they looked after each other, like, they were, just in terms of saying, "Here's a really important book about transgender issues, but you need to know that there is a really violent part of it." They were very careful with each other because they understood that, you know, there may be different kinds of experiences, lived experience of marginalization and violence that they had differently experienced because of where they came from.

So, again, that sort of carefulness is something that they really made me aware of. I mean, I was aware of it for my own students, but then kind of re- saw it in this sort of amazing international group of young people. And, yeah. So, I know it's a very long possibly rambling answer, but I think the listening, asking them what they care about, and really trying to do things a bit differently, not just more of the same.

Ainsley: I mean, I think that's a good answer, and I think it might be heartening for some of the smaller publishers to hear that there's an opportunity to go to different influencers than the ones that, you know, you see over and over again.

Danielle: Yeah. It's not about splashing money around, for sure. I think the other side of that, and these are words that float around on social media platforms a lot, is things like what readers want and why they come to trust an influencer, in particular, is not just about, "Well, I've read some of the things that that person recommended and, you know, the kind of books I like." But they see that influencer as maintaining a kind of authenticity. And some of that authenticity is about sincerity. It is about keeping it real, to kind of use a colloquial phrase, and the ability that some people online have, you know, to remain, I think, true to their values, in a sense, and be very explicit what those values and politics are and to be very genuine about them.

And, certainly, you know, sort of, I think Gen Z, in particular, they're quite clued in to when people are being insincere or whether they're, you know, just kind of trying to sell you something without it connecting to any sort of real integrity or if it's inconsistent with the kind of book that's been recommended before or the kind of conversations that somebody might have started online.

So, I think you're right. I think independent publishers and smaller concerns and agents in the book industry should sort of take heart because that's often where there is a kind of opportunity or space to kind of take sort of some action and be a bit kind of closer to the ground or work directly with, particularly, kind of younger readers, who certainly have lots to say about what they want to read.

DeNel: I'd like to just add briefly to the last part of our conversation. In addition to everything that Danielle has said, is I would recommend to Canadian publishers to look for authors from underrepresented groups and provide them...if there is a set amount of money that you have, instead of giving it to an influencer, split it up between an influencer and an author, providing them with the tools and perhaps the technical expertise and consultancy that they might need because favourite authors are still important to readers.

Danielle: Yeah. And readers, increasingly, I think, and because of social media, they really value direct connections and relationships with readers that they're able to develop on different social media platforms. And, of course, some authors are really good at that, but I think DeNel is right. Sometimes having the resources, which includes time, and people may not have the time to tool up to be able to do that. And so, yeah, I think it's a really great suggestion. It's a very practical way that the authors can be supported in their relationships, building their relationships with readers, in ways that, you know, still, they can maintain integrity.

Because, again, it doesn't have to all be about sort of making a pitch. That is something that...it's a lot of work to be an author these days, you know, if you try and do all the things on all the platforms or even just two or three of the platforms. And I think we sometimes underestimate the amount of labour and time and skills that that kind of work involves. So, supporting writers in that way is definitely...and, of course, that is a very direct connection with readers often.

Ainsley: Well, thank you so much for taking time to talk with me. I think there's a lot of value in this short book for publishers, and booksellers, and anybody who is interested in what readers have to say and...so, we'll put the information about how they can access your book in our show notes.

Thanks again to DeNel and Danielle for joining me to talk about their research.

Before I go, BookNet Canada acknowledges that its operations are remote and our colleagues contribute their work from the traditional territories of the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Ojibwa of Fort William First Nation, the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee, the Wyandot, and Mi’kmaq, and the Métis, the original nations and peoples of the lands we now call Beeton, Brampton, Guelph, Halifax, Thunder Bay, Toronto, and Vaughan. We endorse the Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and support an ongoing shift from gatekeeping to spacemaking in the book industry.

We'd also like to acknowledge the Government of Canada for their financial support through the Canada Book Fund. And of course, thanks to you for listening.

Sales and library circulation data of Science Fiction titles during the the fourth quarter of 2025.